One piece of the spinal cord injury puzzle

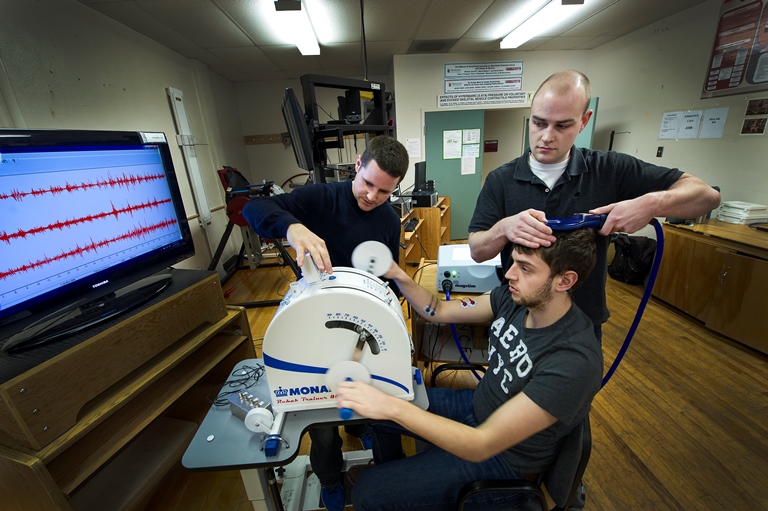

Dr. Kevin Power’s lab looks a little like walking into a torture chamber. A subject is hooked up to electrodes and wires and sitting behind a stationary bike. One of the researchers uses a paddle-like instrument that sends magnetic stimulation to the subject’s brain. It sends a jolt every few seconds, making him jump. In between jolts, the subject is expected to use his upper body to peddle the bike as fast as possible. Then comes another jolt.

In the School of Human Kinetics and Recreation, what Dr. Power and his students are studying is how the nervous system  produces movement. The results could have very positive implications for people with spinal cord injuries.

produces movement. The results could have very positive implications for people with spinal cord injuries.

“The direct and indirect costs of spinal cord injury place a tremendous strain on the health-care system because of lengthy hospital stays, intensive therapy, etc,” he said. “Not to mention complications that come from being sedentary, such as Type 2 diabetes and osteoporosis. But they need motor function to increase their mobility, which would mitigate some of these issues.”

The group is studying a specific group of cells -- the motoneurones. These nerve cells determine whether the muscle contracts. So, understanding how they function and how they adapt to exercise and fatigue is important.

In fact, Dr. Power’s lab was the first in Canada to use this method to assess the spinal cord. Now, he’s one of two labs in the country but still the only lab dedicated to the technique. The method is called transmastoid electrical stimulation, which they combine with another technique called transcranial magnetic stimulation.

The researchers send magnetic fields to the subject’s brain, activating brain tissue which sends electrical activity through the spinal cord and then into a specific muscle. Motor impairments such as spinal cord injury result in a disruption of this pathway, which alters voluntary movement.

“Lots of researchers are measuring the central nervous system excitability, the whole system together and even separately,” explained Dr. Power. “But if you only stimulate the brain and you see a change in the muscle, you don’t know if it’s coming from the brain or the spinal cord. With our testing, we’re separating the brain and spinal cord, with a focus on spinal motoneurones, the cells that project to the muscle via the nerve. A focus on these cells and how they work during locomotion is really what separates us from other labs.”

“If we can figure out how the nervous system is able to activate muscles correctly, we can develop rehabilitation strategies or other interventions which could lead to regaining motor function for someone with full or partial paralysis,” he said. “That’s my goal. I’m not going to cure spinal cord injury but this is one small piece of a much larger puzzle that I can contribute to.”